Lady Chatterly's Lover (Chinese Translation)

Date: 1959

Region: North America

Subject: Explicit Sexuality

Medium: Literature

Artist: D.H. Lawrence (1885 - 1930)

Confronting Bodies: United States Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield

Dates of Action: 1959

Location: The United States of America

Description of Artwork: "Between October 1926 and January 1928 D.H. Lawrence wrote three versions of a novel in which he described the affair of the fictional Lady Constance Chatterly, wife of Sir Clifford Chatterly -an intellectual, writer and Midlands landowner who has been confined to a wheelchair by war wounds- with the estate game-keeper, one Oliver Mellors, the son of a miner. While the book itself, which ends with the lovers each awaiting divorce and looking

forward to their new life life together, does not stray conspicuously from Lawrence's general moral and philosophical attitudes, his use of taboo language far exceed anything acceptable in contemporary fiction." (The Encyclopedia of Censorship, Jonathon Green, Facts on File, N.Y. C. Pg. 166)

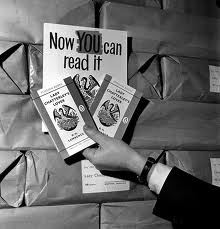

The Incident: The work is deemed "an obscene and filthy work" that cannot be sent through the mail by Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield.

Results of Incident: The ban, lifted after two lower courts disagreed with Summerfield, is not reinstated by the Supreme Court in 1960. The novel went on to sell two million copies in a year.

Source: New York Public Library, New York City

Chinese Translation

Date: 1987

Region: Asia

Subject: Explicit Sexuality

Medium: Literature

Artist: D.H. Lawrence, Hunan People's Press

Confronting Bodies: Central Bureau

Dates of Action: 1987

Location: China

Description of Artwork: Lady Chatterly's Lover, by D.H. Lawrence first translated into Chinese by Rao Shu-yi in 1936.

The Incident: In December of 1986 Hunan People's Press challenged Chinese censors with the publication of D.H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterly's Lover. The initial plan was to publish the book for an access-limited distribution. They believed that, "An access limited edition or 'internal circulation' might grant some element of safety, as the readership would be limited to an elitist circle of people above a certain rank who are supposedly less likely to be corrupted than other members of the public." This decision,(which later changed, opening up the distribution to a wider audience) was a safeguard against pressures from the Ministry of Culture, who had issued a report in July of 1985 denouncing 'flooding of the market by unhealthy, obscene and violence-promoting publications.'

After the first printing, Hunan Press foresaw huge financial rewards in the venture, and expanded the printing to 600,00 copies. "Although the Press's routine annual report to the Central Bureau played down the publication of Lady Chatterly's Lover as much as possible, the Bureau had some how learned of the ambitious plan. It made an informal resolution against the book's open publication on the grounds that the novel abounded in sexually explicit descriptions, so much as to be unsuitable for the Chinese public. Though it never denied the status of literary classic to Lady Chatterly's Lover and even acknowledged that it had a generally healthy theme, the Bureau's resolution, implied that the novel was an exceptional case. When Hunan Press was notified, 360,00 copies had already been printed.

Apart from the cost of the completed work, the canceling of the book would lead to hasty and and major adjustments in the publishers annual plan that would be financially disastrous. In order to limit the scale of possible loss, the publisher ordered the printers to stop work, and dared the wrath of the central authorities by starting distribution of the finished copies without permission, using mostly the venues of private book stores." Hunan Press managed to distribute 230,000 copies, which quickly sold out. The popularity of the novel incensed the Central Bureau, which ordered the booksellers to stop advertising and selling the novel. The books were now open to the movements of the Black Market and pirating. The Bureau then targeted the source, Hunan Press, and ordered the remaining 130,000 copies to be sealed.

Results of Incident: Since the Press had knowingly defied the original resolution and had 'broken discipline,' chief editor Zhu Zhen lost his position, the president of the Press was given a 'serious warning,' and Tang Yin-sun (editor of translated foreign literature) was asked to retire voluntarily... " After continuously complaining to Beijing about the financial loss it had incurred due to the sealed copies, Hunan Press in June 1988 managed to get approval for an internal circulation of 50,000 of the remaining 130,000 books. The general response of the privileged readers was fairly positive, according to Beijing editor who was among them, but this was not to change the official decree. Although the book's black-market price had soared, the Bureau advised the Press to stick to its original low price, dashing its hopes in on the gold rush. To this day, 80,000 copies of Lady Chatterly's Lover are stored in the Hunan Press warehouse.

Source: Yi Chin, "Publishing in China in the Post-Mao Era," Asian Survey, June 1992, Vol. 32, No. 6 Pg. 568-582

Warning: Display title "<span style="font-style: italic;">Lady Chatterly's Lover</span> (Chinese Translation)" overrides earlier display title "<span style="font-style: italic;">Lady Chatterly's Lover</span>".